Behind The Mic: A Personal Peek Into 1970s FM Classic Rock Radio--Pt. 2, KLOL/Houston, Mother's Family

Behind the scenes of my year as a pro radio DJ at Houston's leading FM "progressive" rocker.

In Part 1 of “Behind the Mic: A Personal Peek Into 1970s FM Classic Rock Radio—The College Years,” I related accounts of my two years at college radio…KNTU at North Texas State (Fall of 1973 through Spring ‘74), and as Music Director with a 3-hour afternoon drive-time shift at the University of Houston’s KUHF (Fall ‘74 through Spring ‘75).

While at the latter, I met and interviewed Journey, David Cassidy, and others, while producing a weekly interview show which featured celebs like George Foreman, Helen O’Connell, Robert Klein, and Ed McMahon.

Nepotism: All in the Family (Wanna Make Somethin’ of It?)

Dad had worked as an ad exec, selling commercial air time, for a good couple decades by this time, for KTRH (“Keep Tuned Right Here”), the leading AM news/talk station in Houston, broadcasting at 50,000 watts. At the time, the station, and their landmark “underground” sister side, KLOL-101 FM (“Mother’s Family Radio,” born in 1970, and for whom Dad also sold ad time) were owned by CBS, a corporate entity that will come into play, curiously enough, again later on this page.

Sometime around my 20th birthday in March 1975, I got a call at KUHF from Bob Wright, KLOL’s Music Director. He (and 101’s Program Director, Jim Hilty) had been listening to my soft-rock format afternoon show, and offered me a part-time gig at 101.

Thrilled and excited at the offer, I was to be a “jock sub,” of sorts, being on call to fill in for DJs who were either on vacation, or called in sick on any given day. Houstonians who listened to 101 back in the day might remember noted jocks like “Crash,” Jackie McCauley, Ed Beauchamp, and Emil For Real. Jackie was always sweet to me, but I emulated the deep-intoned Beauchamp, who was something of a mentor for me.

Real-to-Reel

Another part of my job was producing a live, call-in talk show on Sunday mornings. The bespectacled Chapman Mott was the show’s host. He had long, thin, blond hair, and was, essentially (and non-pejoratively), a walking, talking, stereotypical “hippie” leftover from the station’s early years of the late ‘60s.

Mott’s personality was exactly what the station wanted at the time, and he had the delivery and essence that reflected the station’s core late-teens to mid-30s progressive and liberal, possibly self-medicating demo.

Along with presenting two 5-minute newscasts evenly spaced within my 6am-noon shift (ripping and reading copy from our wire-service ticker machine), I screened the phone calls that came in for Chapman, and set up the reel-to-reel tape delay system to weed out any “bad words” that might threaten to invade the morning air!

God knows how they do something like this in the current digital radio days, but five decades ago, in the Neanderthal-by-comparison analog stations, allowing for a 5-second delay between a live phone call being recorded and its eventual airing involved two reel-to-reel tape recorders.

These moveable recorders-on-wheels featured horizontal, “table-top” orientation (as opposed to the vertical configuration of many home reel-to-reels), and the actual delay length depended on how far apart these machines were placed.

The delay occurred because the playback head was located after the record head, which created the needed time delay. The delay could also be created by adjusting the speed of the reels on each machine. I decided to simply place the machines about a foot apart, creating a distance between when Chapman Mott’s phone call was taped, and when it actually aired, about 5 seconds later.

As the full reel’s 1/2-inch tape crept at a 15 ips (inches per second) pace through the heads on the left-hand machine (recording Mott’s phone conversation as it happened), I listened to it, on headphones from the console, in the control room.

If a naughty word was said “live,” captured by the first machine’s recording head, I’d toggle the control room console indicator from “live” to “air” (the right-hand playback reel, which I could now hear as it was going out, on-air), wait for the word to make its inevitable journey to the second machine’s playback head (and ultimately to the take-up reel), and “click” it off for the split-second that the word would’ve aired. It was my job, in other words, to keep the FCC off the station’s back…at least for six hours on a Sunday morning!

Frampton, Coconuts, & The Attack of the Label Reps

I recall spending quite a bit of time “hanging out” in the KLOL main studio, visiting my jock friends when I didn’t have a sub job on any given weekday. After a couple years in radio, I had come to know several of the local label reps…those for Columbia Records (CBS), Warner Bros., and A&M Records.

On one of these days, in October 1975, the Columbia rep fell by, and was dropping off promo items for Dave Mason’s new LP, “Split Coconut,” the guitar player/singer’s third for the label after three years and three albums for Blue Thumb. The rep’s promo item? A coconut. A real live coconut for every jock at the station!

A more monumental visit (and far less preposterous than that coconut palm fruit annoyance) happened just three months later: The January ‘76 arrival of “Frampton Comes Alive,” hand-delivered to the K-101 studios by the A&M Records rep.

To this point, Peter Frampton was nothing more than a “journeyman” guitar player, a UK “Face of ‘68,” a member of Humble Pie, and friend and school chum of David Bowie (Pete’s dad was actually David’s high school art instructor at the former Bromley Tech, now Ravens Wood School).

“Comes Alive” was Frampton’s fifth album for A&M, and the label had at least a million dollars invested in the singer’s promotion alone over the years. He left Humble Pie (A&M artists themselves, with Peter, for three albums) in 1971.

“He had a cool face; I thought he was a star.”

Label chief, Jerry Moss (the “M” in “A&M”), signed him because, as he told Rolling Stone in 2012: “He had a cool face, he didn't mind working, and he had a great attitude. I thought he was a star. Peter had paid his dues. He was with Humble Pie, he put out his own albums. So, it wasn’t like this was a new guy.”

In fact, fellow A&M head, Herb Alpert (the label’s “A”), echoed Moss’s assessment of Frampton’s attractive visage, and offered a peek into the album’s early success: “Peter was a great guitarist and amazing performer, and it didn't hurt he was a cute guy, too. The sales were abnormal: the day we put out Frampton Comes Alive!, we sold 50,000, and it just kept going. It was his time." A special, out-of-the-box retail promo price certainly helped new fans discover this double album.

The Breaking of Springsteen

Houston, in general, and KLOL, in particular, were very instrumental in breaking the early iteration of Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band. Saddled initially with “the next Dylan” tag, his eventual manager and producer, critic Jon Landau, proclaimed Bruce “the future of rock’n’roll.”

It’s debatable (Bruce certainly hated the bluster) whether the commercial backlash to such loud trumpeting had anything to do with his first two albums languishing in the lower regions of the Top 100 album lists. Springsteen’s debut LP, “Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ” (released by Columbia on January 5, 1973) only managed to creep to #60, while his sophomore issue, “The Wild, the Innocent, & the E Street Shuffle” (released ten months later), limped quietly to #59, doing nothing to endear him to the CBS brass.

It’s important to note, here, that it was over a year-and-a-half (August 25, 1975) until Bruce’s true, monumental breakthrough album, “Born to Run,” (with its proud paean to Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” and the singer’s dual weekly news magazine cover stories) was released.

What happened in those 21 months, especially in Houston (and K-101), did much to break Bruce, not only in the Lone Star State, but nationally. And, the man himself, would concur.

The Unofficial Hit That Pissed Off CBS

When I arrived at KLOL (I’m guessing sometime around spring ‘75), I remember a special 4-track cartridge (standard radio issue back in the day to hold PSAs, commercials, etc) I was told couldn’t and shouldn’t be “over-played.” I’m not sure if I was told how that was defined, nor do I recall asking. As the “new guy,” and subbing for various jocks, I dared not tread on hallowed turf.

The song? “The Fever” by Bruce Springsteen. I had Bruce’s first two albums, so I was familiar with his material, and this didn’t ring a bell. I recall it was a live recording (or sounded “loose” enough to be, I thought), and many phone calls I got clamored to hear it. Again, I deferred to the more established jocks to determine the song’s airplay frequency. The rookie astronaut does not mess with the launch codes!

"The Fever" was recorded by Bruce and the E Street Band in a special session at a New York studio May 16, 1973, in just one take, two days after sessions for his second album began.

Although there have been rumors of a Boston show in March ‘73, and even as early as 1972, no live recordings of “The Fever” are known to exist. After May 1973, there is no record of it being played for the rest of the year. The recording, in fact, was used as a demo to be shopped by Bruce’s manager Mike Appel's Laurel Canyon Music Ltd. publishing company, and was legally copyrighted as "Fever for the Girl."

In early 1974, Appel (according to Dave Marsh, in his 2004 book, “Two Hearts” and Christopher Sandford in 1999’s “Point Blank”), without permission, and completely without Columbia Records’ corporate blessings, sent cassette tapes (which each station transferred to 4-track cartridges to play on air) of “The Fever” to several “progressive rock” radio stations, including jocks in Philadelphia and Cleveland, all known to be hugely pro-Springsteen. They began playing it immediately and regularly.

Massaging the Market

"The Fever," of course, had no record sales or jukebox play (not being an official release), but its radio airplay numbers were becoming impossible to ignore. It became a hit in places like Houston, Phoenix and Boston. In Philadelphia (unlike at KLOL), WMMR put it in their regular rotation, and it topped the station in phone-in requests.

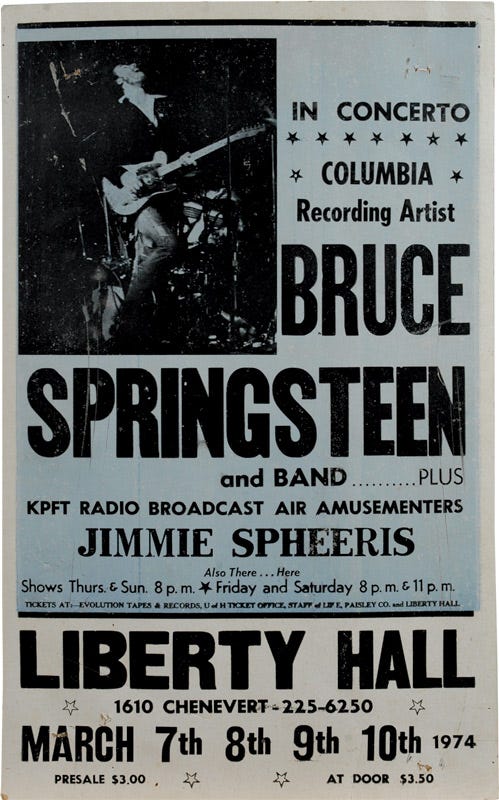

However (according to Marsh), no place was as big for Bruce as Houston, thanks to two radio broadcasts, and seven shows in four nights in March 1974 at the legendary Liberty Hall, formally holding court at 1610 Chenevert, downtown, before being leveled for parking space.

After an exclusive interview by the aforementioned, dulcet-toned Ed Beauchamp on Friday, March 8, Springsteen was invited back to KLOL’s Montrose area studio the next day with the entire E Street Band in tow. Despite having to play later that night, they eagerly ripped through a lengthy Saturday afternoon on-air performance that included highlights from the first two albums, as well as "The Fever,” played for the first time in a year.

“We're gonna give it a try for you; hope we'll remember.”

Later that night at Liberty Hall, after a fan bellowed, "The Fever!", Bruce yelled back, "It's a weird thing, 'The Fever.’ That song 'Fever' we did as a demo tape about a year ago. I promise if we come back, we'll work it up for you."

At the late show the next day, Springsteen introduced the song by saying: "We're gonna try something now, this is something…this is a song we haven't done in about a year, but we found out that they sent a demo down here. We're gonna give it a try for you; hope we'll remember.”

Never one of its writer’s favorites, “The Fever” didn’t make an official appearance (for Bruce, anyway) until a quarter of a century after it created its brief mid-’70s furor. Available on bootlegs, it made its eventual official appearance on 1999’s “18 Tracks.”

With a stamp of approval by “The Boss” himself, his buddies in Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes released their arrangement of “The Fever” on CBS affiliate, Epic Records in June 1976.

But, by that time, I was already on my way to doing “prime time,” 7 to midnight, at an out-of-state FM rocker: