Dale McBride and the Ride From Lampasas to Nashville's Music Row

A '50s rockabilly singer from Texas takes his guitar, gets spotted and signed by a Rat Pack-er, and tries to make it in country music's capital: The saga of an extraordinary man that ended too soon.

Note: This is a collaboration between

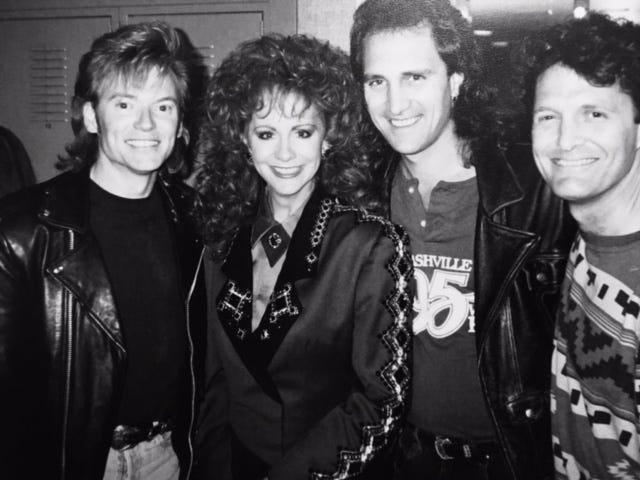

of Substack’s Listening Sessions and myself. Robert was kind enough to allow me to add my personal recollections on the country singer my mom managed for nearly 2 decades.Robert’s excellent biography of Dale is sandwiched around my mid-section of more “on-the-ground” and personal recollections of the singer and my unusual circumstance of being in the record biz at the same time my mother was a personal manager!

For this 2023 Edition (published to commemorate his December 18th birthday, on what would have been his 87th year), I’ve added more photos and info about Dale, as well as his son, popular Nashville singer/songwriter, Terry McBride. To read Robert’s fine, original Edition, click on this sentence.

Robert C. Gilbert from Listening Sessions: Even in a time where more music than ever before is just a click or an app away, we are probably not even remotely close to having a handle on the totality of recorded music. The stories of many who sang and performed and recorded and strove because of some inextinguishable need to create music are more accurately sketches, comprised of no more than stray pieces of biographical data that are superimposed onto the arcs of history.

One such arc revolves around the many artists who began touring in the fifties singing rockabilly, that musical sweet spot that was part country, and part rock and roll, who shifted, by the seventies, to singing country or more specifically, the kind of countrified pop that evolved from the Nashville Sound productions of Owen Bradley and Chet Atkins. That was Conway Twitty’s path. Jerry Lee Lewis’ too.

Charlie Rich as well as the Everly Brothers and Bob Luman all as well.

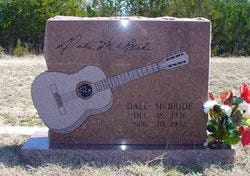

It was Dale McBride’s too. Dale who, you may ask. You are justified in asking.

A Google search brings up little about him. Wikipedia includes a link to a website: dalemcbride.com. Clicking on it brings a dead end. Heading over to the Internet Archive to plug the address into its Way Back Machine and go back to 2011 brings a modest-looking tribute to McBride, referred to as “one of the finest performers of our time.”

Clicking on the link “The Dale McBride Story” brings up what is undoubtedly the most comprehensive biography (it verges, truth be told, on hagiography) on the singer. Its greatest virtue is how it connects McBride’s story to the broader tales of life in America in the middle of the 20th century. There was the challenge of living off an unforgiving land during the Great Depression; in the McBride’s family case, it was trying to maintain a farm in central Texas during the drought and Dust Bowl of the thirties.

There was the displacement of families off their land for the military build-up of the Second World War; the McBride land in Killeen, Texas would become part of Fort Hood and they would move first to Gatesville after pulling up stakes before putting down permanent roots in Lampasas. The radio fueled the dream of a young McBride—he was born in 1936—to become a singer. Local TV gave him his first exposure. He joined a series of rockabilly groups. He recorded for small, indie labels: Knob and Tear Drop between two of them.

He put together a stage show that combined music with comedy—mostly in the form of impressions of performers like Roy Orbison, Marty Robbins and Elvis Presley.

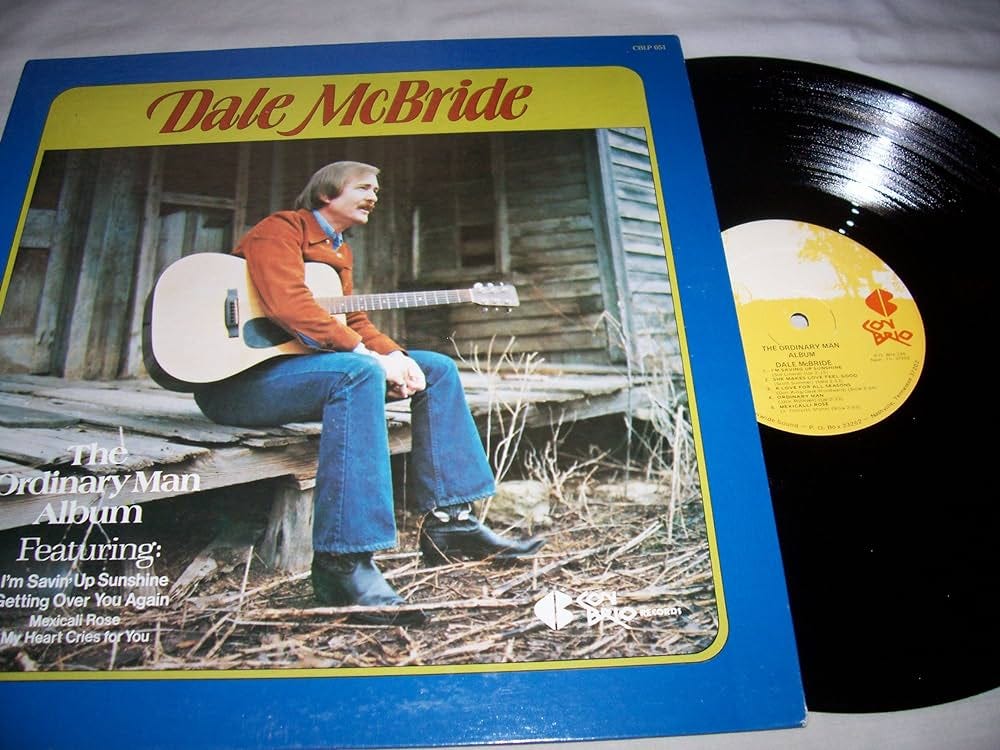

In the mid-sixties, Dean Martin took notice and got McBride signed to Reprise, but McBride’s most fruitful period was in the seventies where he regularly put singles into the lower reaches of the Billboard country chart, first on the Thunderbird label and then teaming up with producer Bill Walker, best known as the musical director for The Johnny Cash Show, on the Con Brio label. The bio on the archived site for McBride quotes Walker as saying that McBride was “versatile, talented and one of the great voices in country music.” McBride continued to perform into the 1980s, and passed away in 1992 of a brain tumor.

Turning to streaming services (Spotify is my service of choice) emphasizes the paucity of information about McBride. Somewhat surprisingly however, there is an episode of a podcast called Record Breakers, a kind of bull session among friends discussing an album each episode, in which McBride’s 1978 album Let’s Be Lonely Together is dissected. Not unsurprisingly with this type of podcast, it is a dreary listen in which an incurious panel spends more time taking potshots at what they are listening to than trying to situate the music—glitzy, late seventies country music—in its proper context or discussing their lack of affection for it in a more musicological or, at the very least, diplomatic light.

In terms of actual music, there is some but not a lot. One recording from McBride’s days in rockabilly surfaces on a compilation called Slow Boogie Rock. “If You See My Julie” is credited to a group called Gaylon Christie and the Downbeats, about which there is virtually no information. An obituary for Christie, who died in 2014, covers his work as a disc jockey in Texas, charitable works and the early exposure he gave to future country stars like George Strait and Alan Jackson, yet makes no mention of when he was a musician. The recording appears to be from 1958 and the Discogs site lists a handful of singles the band released on such small labels as Kobb, Fame and Bid.

“If You See My Julie,” on which McBride appeared as a guest vocalist, is fairly representative of rockabilly steeped in country. Its primary virtue may just be in how McBride resists the overt affectations of each leading lights in the field as Gene Vincent, Johnny and Dorsey Burnette, and Eddie Cochran, even as their kind of hiccup style of singing is what makes rockabilly so perpetually fresh and exciting.

The only other collection of McBride’s music on Spotify is a compilation of his recordings on Con Brio—that period in the seventies in which he was regularly on the Billboard country chart. Listening to it immediately brings to mind where he fit on the country spectrum. Anyone familiar with Billy Sherill’s productions with Tanya Tucker, Charlie Rich, George Jones and Tammy Wynette or the work Glenn Sutton did with Lynn Anderson will instantly get the lingua franca at play: slick, electric productions—no steel guitars or fiddles—background singers, everything planted firmly in the middle of the road (not that there is anything wrong with that!).

My Personal Account: Dale and His Manager

Brad Kyle: It was about this time (early-1970s) that my mother first met Dale. She had moved to Austin from Houston around 1974, after my brother and I had graduated from high school. Mom and Dad had divorced, and Clint and I had moved on to start our respective careers.

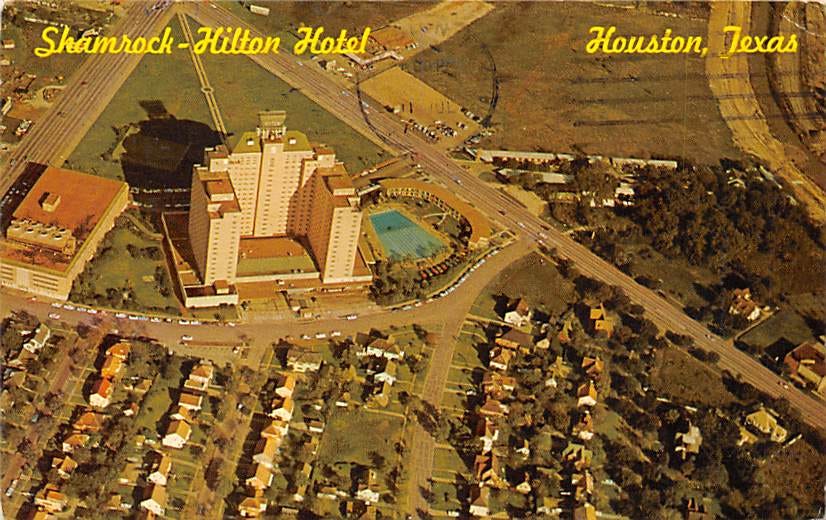

Mom continued to be the entertainment booking agent she had been for well over a decade, having started with 1930s and ‘40s “Rippling Rhythm Orchestra” band leader, Shep Fields’ new agency office in the Shamrock Hilton Hotel in the early ‘60s. In short order, Mom started her own booking agency in the Shamrock, Artists Corporation of Texas (ACT).

From her new Austin home, she routinely pounded the phones, trying to place her large roster of singles, duos, and bands (country and rock) at clubs and conventions around the country. One night, she took in a show by a country-pop artist a friend, Lil, had invited her to hear…Dale McBride.

The venue was the Villa Capri, an Austin resort, of sorts, just off I-35, near where the LBJ Library is now, and adjacent to University of Texas sports practice fields. The Villa Capri was a hotel, and had a restaurant and club with live entertainment (a room my mom booked on a regular basis).

After Dale’s show, Mary, who’d known Dale for a while, introduced the two. She and Mom would end up being friends for decades, until Mom’s 2016 passing. More Villa Capri dates for Dale would follow, with Mom even operating one of the spotlights from the back of the room for some of them!

A hallmark of Dale’s stage shows was his array of musical impersonations. He was able to do song snippets in the voice and style of singers like Elvis, Eddy Arnold, and Glen Campbell, among others. His comic rendition of the John Hartford/“Gentle on My Mind” Campbell hit had the song starting, “It’s knowing that your door is always open and your furniture is gone.”

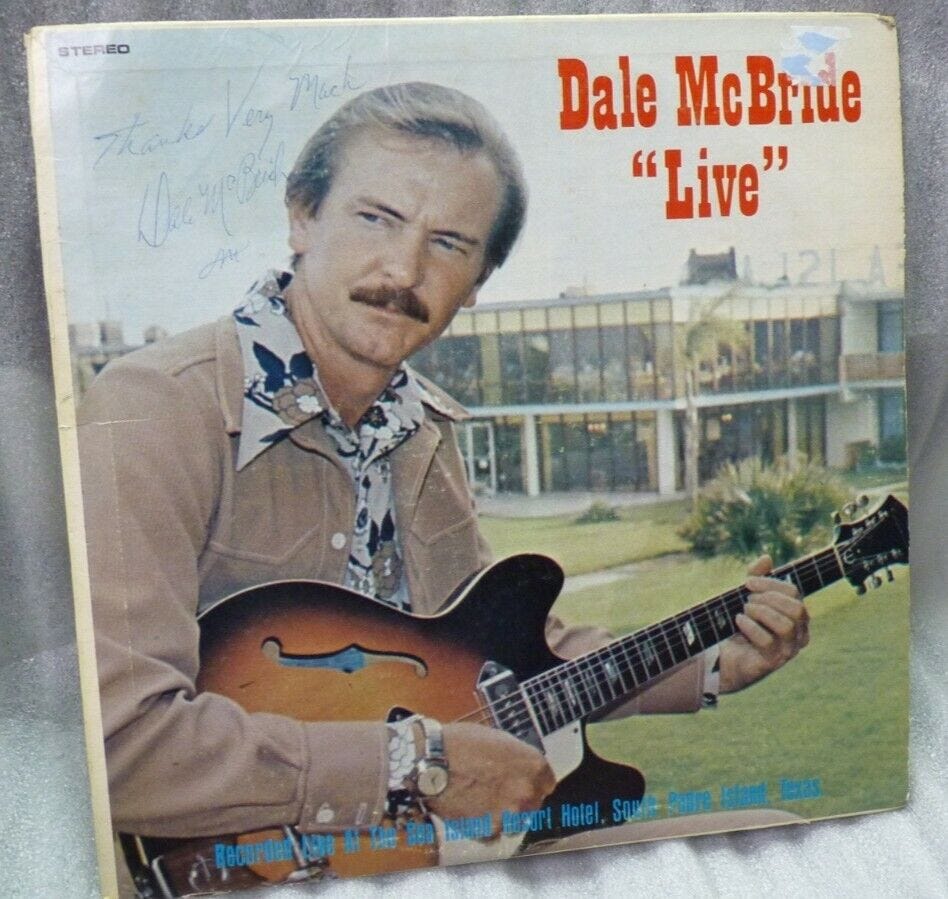

Dale had a definite cross-over country/pop appeal, not unlike Campbell. Dale was musically gifted as a guitar player, and I seem to recall him playing a couple other instruments, as well, including banjo. I met Dale in the late ‘70s, as I would frequently travel from my Houston home to visit Mom in Austin for various holidays.

Mom started booking Dale at shows nationwide, and they attended a couple of Fan Fairs in Nashville (the annual multi-day convention where country stars and fans get to intermingle amid shows and other activities). Sometime in the early-’70s, Dale agreed to have Mom become his manager.

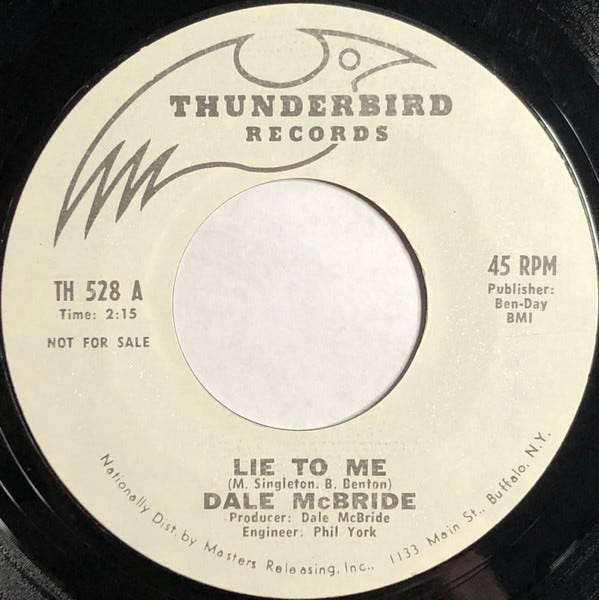

Having recorded previously for tiny Thunderbird Records (a 1970 single he produced, “Lie to Me” b/w Dale’s own “Guess You’ve Made Your Mind Up”), Dale signed with Con Brio Records, the label founded and owned by Bill Walker, the Director of Music for the late-‘60s/early-‘70s Johnny Cash TV specials.

Dale’s biggest success came during his Con Brio tenure, which lasted for nearly two decades.

In the late ‘70s, I worked at Houston’s top retail vinyl store, Cactus Records. In the early ‘80s, I was assistant manager at L.A.’s popular record retailer, Music Plus. Mom would call me with Dale’s chart placement for the following week. She’d hear from Bill Walker the week before exactly where Dale’s latest single would be on Billboard’s country chart! For example: “Brad, Bill Walker says Dale will go up from #44 to #32 on Billboard’s country chart next week!”

How exciting (and unusual) for my mother and me to be “in the same biz,” able to call each other and “talk shop” to a degree!

I was forever trying to “guide” Mom into doing what she could to, somehow, encourage Dale away from Con Brio, and do whatever it took to get an RCA, a Columbia, or an MCA to sign him.

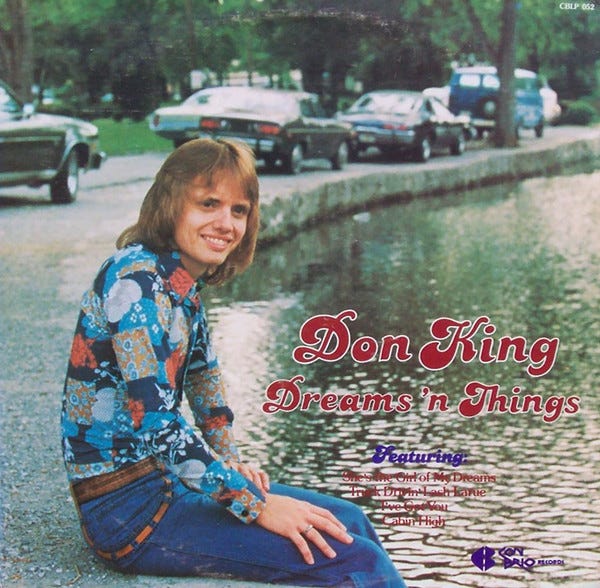

But, however much she may have wanted to have Dale on a much larger label, there was no way Walker was going to gut his stable by allowing his kingpin to sign elsewhere! Con Brio had respected veteran singer, Jan Howard, the youngster, Don King, and about ten other artists on its roster.

Curiously, after two albums for Con Brio (1975, shown above, and in ‘78), King moved on and signed a 2-album deal with CBS affiliate, Epic Records, for 1980 and ‘81 releases. So, it could be done, and for all of King’s talent and youth appeal, Dale had so much more potential for cross-over and multi-generational success.

At some point during the mid- ‘70s, I met Dale’s children, Jo Leigh (Jo Lee?) and Terry. Now 65, Terry McBride was about 19 when we met, probably in 1977, when I was 22, and working at Houston’s Cactus Records. I seem to recall Terry would take to the stage and accompany his dad on guitar from time to time.

After a few years in the ‘90s fronting country-rock band, McBride and The Ride (for MCA Records), Terry became a very successful songwriter, penning hits for Brooks & Dunn, Reba McEntire, and others. For his contributions as a songwriter, Terry has won 12 BMI awards.

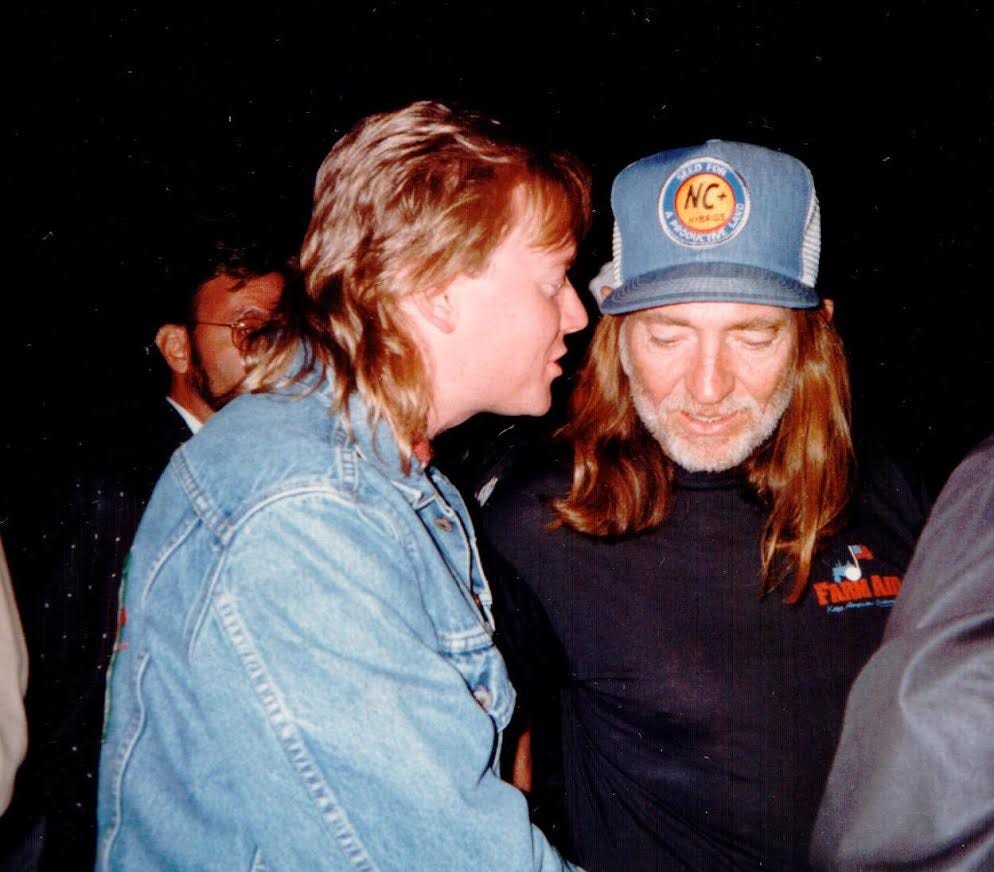

Robert C. Gilbert: As for McBride’s music, at the time Brad’s mom was managing him, it can be easily, maybe even reflexively, dismissed as sounding more of an approximation of country than the real thing as more established artists like Willie Nelson [pictured above with Terry in the late-‘80s], Waylon Jennings and others went so-called “outlaw.”

A song like ‘I Don’t Like Cheatin’ Songs’ with its sing-song quality is redolent of the hokum that still causes some to stick their noses up when made to contemplate country music. “I’m Saving Up Sunshine” is, too. But songs like these are ultimately distractions, hazards to avoid to get to the good stuff. And some of McBride’s stuff is good.

“Get Your Hands On Me Baby,” a single from 1979, had the kind of refrain that lingers. Its harmony is also intriguing. With McBride and a group of female background singers often singing in unison, it brings to mind some of Elvis Presley’s recordings at American Sound Studio in 1969—perhaps his cover of Neil Diamond’s ‘And the Grass Won’t Pay No Mind’ most of all.

‘A Love for All Seasons’ has McBride singing the verse without a steady beat. His voice could never be mistaken for one of country’s finest, but it is sincere as is the chorus: “a love for all seasons / come summer or fall / with our hearts entwined / love is all that matters after all.” It’s, in a way, musical comfort food, a subgenre of music really of its own that spans a wide range of artists that elude the critics yet find a home in many a person’s record collection.

Beyond what can be found on Spotify, there are some of the singles from McBride’s time as a rockabilly man on YouTube. “Prissy Missy,” from 1959, is the most well-known, and there is great energy on it as well as an edge that foreshadows the garage rock of the mid-sixties which thankfully distracts from the retrograde lyrics. There’s even a music video—a low-budget affair—for a song called “The High Cost of Loving,” partly a countrified scenario out of Curb Your Enthusiasm and partly Hallmark-worthy wholesome. McBride is standing in a supermarket line in front of someone taking all the time in the world. He’s annoyed, but not because of a breaking of the checkout-line social contract:

He’s simply anxious to ring up his groceries so that he get home to have a nice evening with his lady. It reminds that his biggest hit on the Billboard country chart was “Ordinary Man,” hitting #26 in 1976.

The chorus seems to sum up McBride’s music: songs for those who put in an honest day’s work for an honest day’s wage and who find sustaining joy in life’s simple pleasures. In other words, the vast majority of people. Perhaps even you and me.

I’m not the world’s greatest lover

I don’t hang out in barrooms

I’m not a cowboy or a rodeo man

But I love the life I’m livin’

And I love what life’s been given

To a plain and simple ordinary man.

- the chorus of ‘Ordinary Man,’ written by Jack Ruthven

Interesting read about an artist I wasn't familiar with.

I loved this collaboration when Robert first published it, and I'm loving your "remix" of it, so to speak. Two brilliant writers... what a treat!!

I read with fascination when you talk about your mum (and, separately, the stories you tell about your dad and his record collection), and I'm just thinking... no wonder! I mean, the apple doesn't fall far from the tree!