Salute To 42: Shortstop Willie Wells and His Texas Influence On Jackie Robinson

Austin native Wells, a member of three Halls of Fame, helped baseball's legend, Jackie Robinson, improve his play in the field.

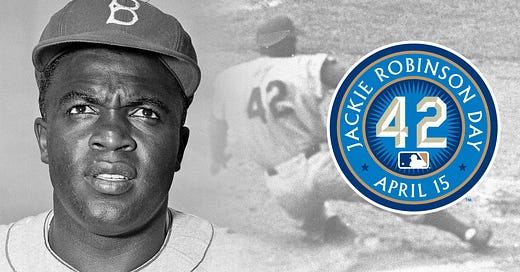

Throughout Major League Baseball, April 15 is Jackie Robinson Day. Every player on every team wears Robinson’s #42, a tradition that began on April 15, 2004, honoring the anniversary of his big-league debut.

MLB also universally retired his number in 1997, meaning no player may ever wear that number again. The ten-year veteran Brooklyn Dodger is the first pro athlete to be so honored, and no other pro sports league has ever honored an athlete in such a way.

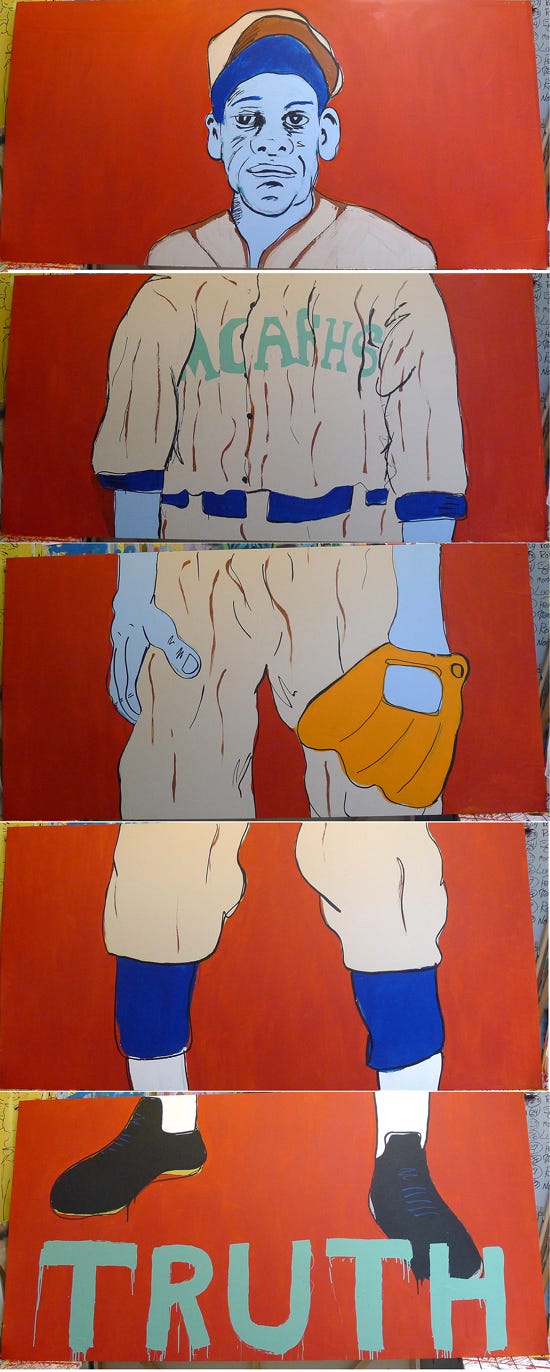

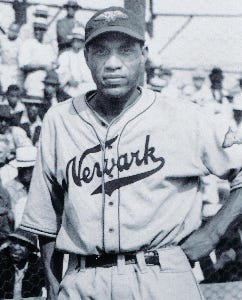

Negro National League Shortstop Willie Wells

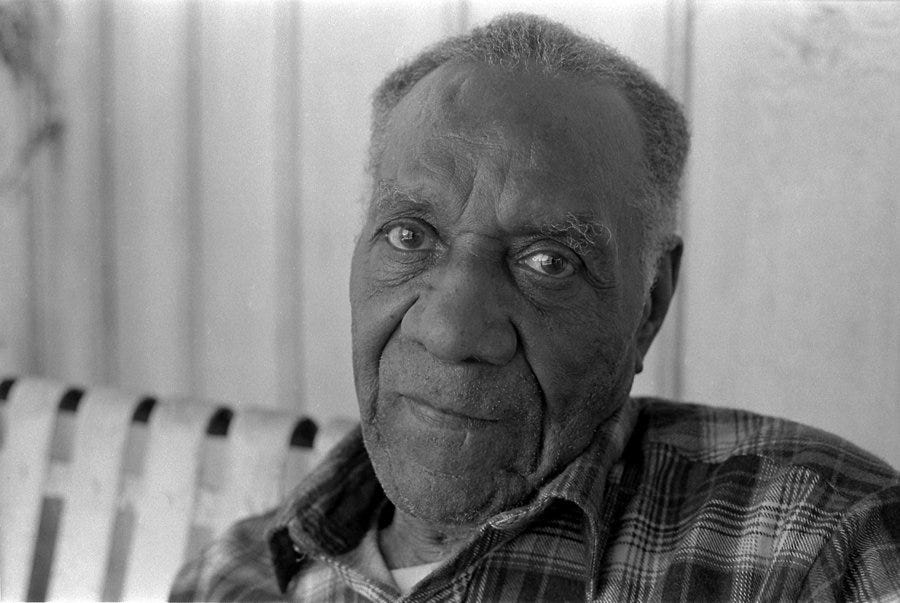

A member of the baseball Halls of Fame in the United States (inducted 1997), Cuba, and Mexico, Willie James Wells (pictured above) was born in Austin, TX on August 10, 1906, and attended then all-black Anderson High School (on Austin’s east side, in the location of the present-day Kealing Middle School), still in use today (but in its northwest Austin location since 1973).

He briefly attended Samuel Huston College in Austin (known since 1952 as Huston-Tillotson College, before attaining university status in 2005, as Huston-Tillotson University) prior to being called up to the St. Louis Stars in the NNL.

Wells passed away in Austin 83 years later, in 1989, but not before making an indelible mark on baseball in general, and Jackie Robinson, in particular.

The only woman elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Effa Manley, called Willie Wells, “The finest shortstop, black or white.”

Cool Papa Bell recalled Wells: “Of the shortstops I’ve seen, Wells could cover ground better than any of them. Willie Wells was the greatest shortstop in the world.”

“The Shakespeare of Shortstops”

Wells, the first power-hitting shortstop, was a mentor to younger players, including Jackie Robinson and Monte Irvin (both 13 years Wells’ junior).

Irvin once remembered: “Wells showed me everything he knew. We talked about hitting—he was a really good curve ball hitter—about moving around on different pitchers, especially left-handers, moving up in the box, moving back, trying to throw the pitcher off, trying to take a peek back to see how the catcher is holding his target in a close game.”

Irvin passed away in Houston in January 2016, as the oldest living former Negro National League player, the oldest living Chicago Cub (1956), and New York Giant (1949-1955, pre-San Francisco move).

“Wells was the kind of player you always wanted on your team; he played the way all great players play – with everything he had.”-Tigers Hall of Famer, Charlie Gehringer

Wells was a forward-thinking innovator in his own right, as he is considered one of the first professional ballplayers to wear a batting helmet, fashioning a construction helmet hard hat for protection after a 1942 beaning by Ray Brown (some accounts assert it was Baltimore’s Bill Byrd’s spitball beaning that preceded Wells’ hard hat innovation).

Also, the date of that beaning and subsequent “helmet” donning by Wells is occasionally disputed, as some have pinpointed the incident as having occurred on August 26, 1937.

Incredibly, his glove was known for a hole in its middle, which the right-handed Wells claimed made his fielding easier. A consummate 5-tool player, he could hit for average and power, run, and was a wide-ranging defensive shortstop with a remarkably accurate arm. He made up for a lack of arm strength by perfecting a quick release on his throws deep in the hole.

The DP Pivot: Wells Working With Jackie

Wells began playing ball on the sandlots of central Texas and, while playing with the San Antonio Black Aces in 1923, he was discovered by both Rube Foster of the Chicago American Giants, and St. Louis Stars‘ owner Dr. George Keys. Wells chose to sign with the Stars, and began playing with the St. Louis team the next year. In 1928 for the Stars, Wells hit 27 home runs in 88 games.

His hitting continued to improve and impress, as he earned consecutive batting titles in 1929-30 with averages of .368 and .404, respectively. With Wells leading the way, the St. Louis Stars won Negro National League championships in 1928, 1930, and 1931.

In the winter of 1929, Wells went to Cuba and played in the integrated Cuban League, where he competed and excelled against Cuban players and white major leaguers, alike. That same year, he was the MVP in the Cuban League.

Wells spent several years with the NNL’s Newark Eagles, and hit a combined .371 in his four-year tenure with the team at the end of the 1930s.

Willie Wells was selected eight times for the East-West Classic, the Negro Leagues’ All-Star Game, including his first in 1933, and the 1945 game (in Venezuela), in which he played second base for the East, and Jackie Robinson, then of the Kansas City Monarchs, played shortstop for the West.

When Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers’ AAA Montreal Royals farm team in 1946, Wells worked with him on his second base position, helping him perfect his double-play footwork, including the pivot.

Empathy For “The Devil”

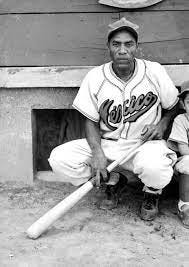

Also in the 1940s, the 5’8″, 160-pound Wells played in the Mexican League for a few years, where he again excelled as an outstanding player against white major leaguers who were also playing in the Mexican League.

Wells acquired some happy memories playing south of the border, where he said that he experienced democracy, acceptance, and freedom. Wells was nicknamed El Diablo by Mexican fans for his blazing intensity. “The Devil” nickname followed him back to the states.

After retiring from baseball, Wells worked at a New York City deli for 13 years before moving back to Austin in 1973 to help care for his aging mother. After she passed away, he continued living in the same house where she raised him, until he died from congestive heart failure in 1989.

Shortly before his death, Wells reflected on his life well-lived: “I didn’t want to do anything but play baseball. That was my life and it was good to me. Baseball is still nothing but hit the ball and catch the ball. I just wanted to be the best. I never wanted to lose.”

As you remember and celebrate Jackie Robinson, include the magnificently gifted and giving Willie Wells, who selflessly added much to our appreciation of #42.

Brad, what a wonderful article casting the light on one of baseball's unsung heroes. I for one had never heard the name Willie Wells. I shall not soon forget it!!!