Toytown Psychedelia: Songwriter Tandyn Almer--Brian Wilson's Friend & Co-writer of 2 Beach Boys Songs + "Along Comes Mary"

No one knows who he is, but everyone has hummed his tunes, and many have envied his enigmatic aura. Never seeking the spotlight, he won the praise of Leonard Bernstein, passing in 2013 at age 70.

He wrote songs with Brian Wilson.

For the few (including this writer) who knew precious little about Tandyn Almer, that may be all you need to know: Right away, we’re now aware that he had enough of a precious musical cache that The Beach Boys’ tonal architect would eagerly invite him into his creative universe, and not be threatened by his gift or jealous of it.

Seemingly, nothing online describes Almer with anything other than phrases like, “pop music’s enigmatic songwriting genius.” In the words of Dawn Eden (who inspired this article’s title) in 2013, “He became a mysterious figure, the subject of rumors and legends, not unlike another hit songwriter, P.F. Sloan, whose enigmatic departure from the Los Angeles rock scene became the subject of a popular song by Jimmy Webb.”

At times, people who knew of Almer’s musical contributions wondered what had become of the young composer with so much promise. According to the Washington Post, his half-brother, Nicholas Minetor, once recalled reading online speculation about whether Almer was even still alive.

“That just tickled him to death,” Minetor said. “He liked being mysterious. And we knew he was living in a basement in Virginia.”

Indeed, Tandyn had occupied, for several years, an unkempt basement apartment in McLean, Virginia, where he died January 8, 2013 (of heart-related issues) at age 70. Two years before, he had his right leg amputated below the knee. Upon his passing, several acquaintances were surprised that he had lived that long.

Portrait of a Young Pop Prodigy

Tandyn Douglas Almer (Wilson fanatics will know Tandyn and Brian share the same middle name) was born in Minneapolis on July 30, 1942, about five weeks after Brian, and about 1,800 miles from Wilson’s Inglewood, CA birthplace (and eventual Hawthorne home).

According to his half brother and sister-in-law (the Minetors), his parents couldn’t settle on a name, so they came up with “Tandyn” almost as a whimsical afterthought.

We seem to get the most enlightening stories, according to the aforementioned Dawn Eden, from Tandyn’s sister-in-law, Randi Minetor, as shared from his mother:

”When Tandyn was small, his mother used to read him a book every day at lunch. One day, when he was four, he announced to her that he would read her the book instead. And he did. Later—I think even that same day, if I heard correctly—his mother was doing dishes when she heard piano music coming from the next room.”

That was the beginning of a painful and isolating time for Tandyn.

“She didn’t think anything of it, thinking it was the phonograph. But, when she walked into the room, she saw that the phonograph was not playing: It was Tandyn at the piano, playing by ear a classical piece he had heard. With two hands. She promptly took him to a local conservatory, and he was admitted on the spot.

A few weeks later, Tandyn started kindergarten, and a few weeks after that, his mother began getting phone calls from the school: The child was labeled a problem because he failed to pay attention.

“His mother insisted to school officials that he was extraordinarily advanced and needed more challenging schoolwork, but there were no ‘gifted and talented’ classes in 1946. That was the beginning of a painful and isolating time for Tandyn.”

When his parents separated, he and his mother moved into an apartment--a basement apartment, as it happens, a possible foreshadowing of Tandyn’s future--with two pianos. Tandyn somehow managed to push them together and played both at the same time!

Along with his obvious and incredibly early understanding of classical music, Almer was also attracted initially to jazz, particularly the music of John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Ahmad Jamal. Add this all to the equation when considering the compositions of a young Tandyn. Also, don’t be surprised to discover that he later became a member of the Washington, D.C. Mensa chapter!

At 17, he quit high school and moved to Chicago in 1959 to become a jazz pianist. In the early 1960s, he relocated to L.A. where his musical interests then shifted to pop and rock after he discovered the music of fellow Minnesotan, Bob Dylan.

In 1965, Almer wrote “Along Comes Mary,” famously recorded and made a Top Ten hit by The Association the following year. But, likely before writing that landmark song (perhaps by a few weeks), he wrote “You Turn Me Around” as recorded by The Ballroom in 1966, a group that included one Curt Boettcher, yet another “invisible and enigmatic,” but astonishingly productive and influential talent in ‘60s and ‘70s L.A.-based pop music.

It was Boettcher (pronounced “Betcher”, short “e”) who produced “Along Comes Mary” and the rest of The Association’s debut album in July 1966.

The New York Times once wrote of Boettcher: “If his life had gone just a bit differently, [he] might have been another Brian Wilson. As it stands, Boettcher, a pop-music producer whose heyday was the late ‘60s, now survives in rock history mostly as a liner-note credit.

“He could have been, but never was. Yet he enjoys a godlike status among a select group of music fans, for whom obscurity is more enticing than fame.”

Almer recorded “You Turn Me Around,” also in 1966, which gave Boettcher and The Ballroom a template from which to work (note how bereft of background vocals Almer’s arrangement is; Boettcher couldn’t wait to get at it!):

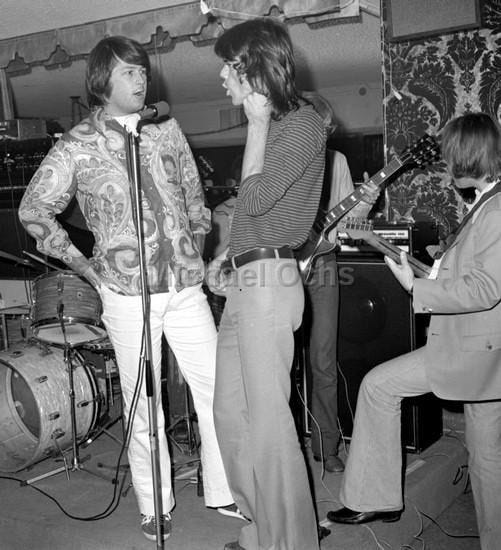

Boettcher’s Ballroom (below), l-r: Michele O’Malley, Jim Bell, Sandy Salisbury, Boettcher

Almer’s composition, “You Turn Me Around,” as recorded by The Ballroom, 1966 (not released, though, until 2001). A deft and canny singer, any vocal arrangement contributions Boettcher made here or on eventual Association recordings cannot be understated, credited or not:

Back to the Dawn Eden essay: “Curt’s big break was producing the Association’s ‘Along Comes Mary,’ a song he had first heard from Tandyn himself, as the two were close friends and songwriting collaborators.

“Their friendship would sadly end over Curt’s insistence that he receive co-writing credit for having contributed significantly to ‘Along Comes Mary,’ a claim Tandyn vehemently denied. Curt had sung on Tandyn’s demo of the tune, and he alleged that, in singing it, he had altered the arrangement enough to make it essentially a different song. You be the judge:

”Although Curt’s claim to co-authorship of ‘Along Comes Mary’ may have been wishful thinking, his production of the [Association version] ‘has stood the test of time,’ as Al Kooper (Royal Teens, Blues Project, Blood, Sweat & Tears) recently noted.”

“Thanks to a YouTube user, you can hear the backing track and try to grasp how avant-garde both Almer’s melody and Boettcher’s production must have sounded to listeners in early 1966.”

This backing track is not performed by any Association members, save for handclaps and a recorder overdub by Terry Kirkman. The basic track features, among others, Ben Benay (guitar), Lee Mallory (guitar), Mike Deasy (guitar) and Jerry Scheff (bass).

Words and music by Tandyn Almer, originally produced by Curt Boettcher, with backing track mixed specially by Allan Brownstein for the 2011 Deluxe Expanded mono edition of the album:

About a year after their debut album was released, here’s The Association, with Almer’s song, at the Monterey Pop Festival, June 1967. They were the openers for the landmark three-day music festival, which featured The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Otis Redding:

Related: “Along Comes Mary” Cover Playlist:

Inside Tracks #9: Tandyn Almer "Along Comes Mary" + The Association, R. Stevie Moore, Manhattan Transfer, 24-7 Spyz

He was only in the public eye (and reluctantly, at that) for about a decade…roughly 1965 through the mid-’70s. Therefore, very few photos were taken of him, and I’ve seen about all of them, now. No one photo captures the childlike persona of the young man blessed with a maddeningly limitless and sophisticated musical talent who had no idea how to harnes…

Eden: “Almer’s [‘Along Comes Mary’] fascinated Leonard Bernstein, who said in 1966, ‘I am a fanatic music lover. I can’t live one day without hearing music, playing it, studying it, or thinking about it. And, all this is quite apart from my professional role as musician; I am a fan, a committed member of the musical public.

‘And in this role of simple music lover, I confess, freely though unhappily, that at this moment, God forgive me, I have far more pleasure in following the musical adventures of Simon and Garfunkel or of The Association singing ‘Along Comes Mary’ than I have in most of what is being written now by the whole community of avant-garde composers. Pop music seems to be the only area where there is to be found unabashed vitality, the fun of invention, the feeling of fresh air.’

“Bernstein featured ‘Along Comes Mary’ in his Young People’s Concert episode titled ‘What Is a Mode?’. In the case of ‘Along Comes Mary,’ the answer is Dorian.”

Jump ahead to the 16:18 mark, if you’d like, to hear Bernstein play and sing a portion of the song (which he compliments as being “primitive and earthy”), but he also demonstrates what it would’ve sounded like in the Minor Mode, rather than Dorian! I’d like to think Tandyn was beaming with pride!

Along Comes Brian…

While a staff songwriter for A&M Records sometime in 1970, Tandyn was introduced to Brian Wilson by musician Joseph DeAguero.

According to DeAguero, “Everyone thought he was going to be the next Dylan or Elton John. Tandyn was totally an eccentric, but he was in a league of his own. You listen to his music and say, ‘God, this guy was really good.’”

…and The Beach Boys

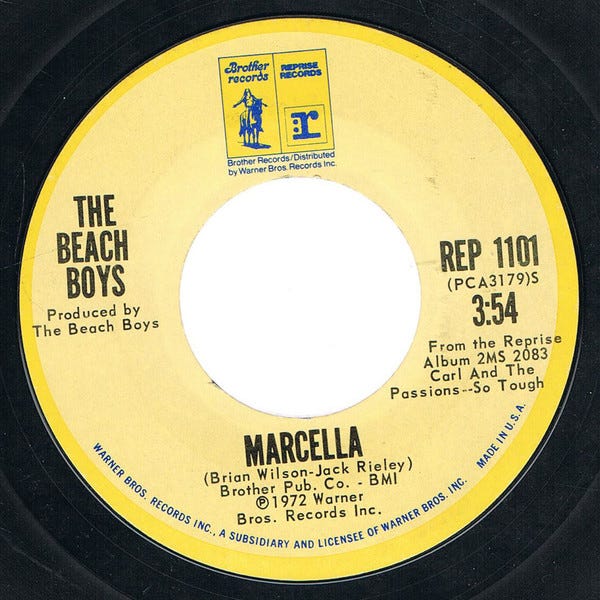

Tandyn Almer has long been credited with having co-written the Beach Boys’ single, “Marcella,” which appeared on the 1972 double-album, Carl and the Passions--So Tough. Curiously, though, Almer’s name doesn’t appear on the label; DJ and early-’70s Beach Boys manager, Jack Rieley’s name does, though:

However, we would do well to never doubt the mighty Wiki, which persists: “Written by Brian Wilson, Jack Rieley, and Tandyn Almer, the lyrics were inspired by Wilson’s fixation with a local massage therapist,” according to the Riverside County Press-Enterprise in 2014. It’s also the last song to feature Bruce Johnston in his original tenure in the band.

The next year found Tandyn co-penning (again with Brian) the far-overlooked “Sail On Sailor,” which anchored the 1973 album, Holland:

By 1974, though, Almer “got frightfully despondent,” according to DeAguero, and left L.A., never to return. “He packed up everything,” DeAguero said, “and I took him to the train station.”

After finding his way to Washington D.C., Almer wrote songs in the 1980s and 1990s for Hexagon, a political satire revue. In the late ‘80s, he rented a room in Northern Virginia from jazz saxophonist, former special ed teacher, and political activist, Herb Smith. He practiced in the rehearsal rooms at Northern Virginia Community College’s Annandale campus, where Smith teaches.

“He’d jump on the piano, and I couldn’t get him off,” Smith (pictured above) told the Washington Post. Almer played music day and night, sometimes going without sleep for four days or more.”

“He used to tell me the music got better the longer he stayed awake,” said Tom Bernath (shown above), a multi-instrumentalist and founder of Upfront Studios in Fairfax, VA, who occasionally rehearsed with Almer, and spent time after his death cataloguing hundreds of tapes found in his apartment. “He didn’t feel like playing until he had been awake for two or three days.”

Almer often read books on science, and he began attending local meetings of Mensa in 1977. Several people said he had occasional long-term girlfriends, but he never married.

“He wasn’t shy at all,” Bernath continued. “He was, unbelievably, a happy guy. There was never any complaining or gnashing of teeth about money. “He was so sensitive, not in the way of having his feelings hurt. But, I almost felt he could read my mind. I’ve never been around anybody who was that perceptive.”

Although he briefly drove a taxi and had a job building computer circuit boards, Almer lived almost entirely on his intermittent music-publishing royalty checks. Whenever he came into money, he’d buy a new keyboard or, sometimes, a used Lincoln Continental.

He was an erratic driver and was often in accidents. Smith said he once got Almer out of jail after he was arrested for disruptive behavior on a Fairfax County bus.

“He was not sad, really, about these calamities,” Smith said. “His bipolar, whatever that is, it never did affect me, and it didn’t limit him. I always dug Tandyn being around.”

One day, Smith noticed that Almer had cut his shoulder-length hair. He wanted to look presentable, he said, for his visit (his first in years) to his mother, June Minetor. Ms. Minetor (pictured below) passed away in Rochester, NY in May 2016 at age 97, 3 1/2 years after her son.

In his final years, Almer corresponded with acquaintances on Facebook, and began to reconnect with old friends. Mostly, though, he stayed in his room, playing music that no one else would hear. He left a body of work of at least 75 songs and, reportedly, as many as 300.

“There are some incredible songs,” reflected Parke Puterbaugh (above), a former senior editor for Rolling Stone who wrote the liner notes to the Along Comes Tandyn album, released by Sundazed Records in 2013 (featured below on a Spotify Playlist). Puterbaugh got to know Tandyn in the final years of his life.

“It’s hard to speculate why some of these brilliant compositions never saw the light of day.”

Chris Rainbow: Another talented singer/songwriter heavily influenced by Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys. Read about him here:

It's so nice to read his story. I mainly know him only as the author of "Along Comes Mary".

Such an interesting piece! You've collected so much data and put together such a compelling story of Tandyn's work and life.

A few thoughts. If there's an argument for people having multiple lives, it has to be musicians who seem to know how to play as soon as they come in contact with an instrument, like Tandyn.

Chris Dalla Riva recently did a piece on the whole credit issue, and back then it was much less likely to give credit to the producer (like Curt) but it was already changing, and now everyone and their dog gets credit. So Curt would get credit now most likely and Tandyn would not be able to deny it.

That video with Leonard Bernstein is such a find. I want to watch the entire thing!

I have always loved "Along Comes Mary" and thought it was different and special, and this clinches it. The sixties was like a wild frontier for musical creativity, and that carried to some extent into the following decades, but the music industry and radio consolidations were already having an effect by the early 70s and so many artists and songwriters (Like Tandyn and Sloan) were leaving the business by the mid-70s -- or having to bow to serious commercial pressures. I just keep stumbling on evidence of this and want to write more about it.

But this was a fascinating piece and I'm glad you're documenting these artists who might be forgotten otherwise. A real contribution!